When the architect Louis Kahn, who designed some of the 20th century’s most notable buildings, appeared in public, he could generally be seen carrying a dark red, hardcover Winsor & Newton sketchbook. In a time well before digital supremacy, the designer of soaring modern icons, including the Salk Institute in the La Jolla neighborhood of San Diego and the National Parliament building in Dhaka, Bangladesh, etched drawings, doodles, thoughts, and the miscellanea of life.

Kahn died in 1974, at age 73, and his daughter Sue Ann, a noted flutist and teacher, inherited more than a dozen of her father’s notebooks from her mother, Esther, when she passed away in 1996. Each book fascinated Sue Ann, but it was the final one, from her father’s last year of life, that drew her closest attention.

In it, Kahn had sketched, from beginning to end, his plans for what was then called the Roosevelt Memorial — now the Franklin D. Roosevelt Four Freedoms State Park, on Roosevelt Island in New York City, completed in 2012, long after his death. He also worked out plans for Abbasabad, a sprawling and undulating new civic center in Tehran, for the Shah of Iran (never built), and for the Yale Center for British Art (completed in 1977), among other notes.

More personally, the notebook, which captured “the private process of what mattered to him,” Sue Ann said in an interview, connected her to the final moments of her father’s life. He had been traveling around the world, chasing commissions and carrying out work. She barely got to see him that year, and she never got to say goodbye. (Kahn, based in Philadelphia, was found dead of a heart attack in a bathroom in New York’s Penn Station.)

She set out to make a new book, which would include a facsimile of the notebook. It took her more than 15 years to find a publisher; Sue Ann and the Swiss-based publisher Lars Müller completed it in time for the 50th anniversary of Kahn’s death, this March. The result, “Louis I. Kahn: The Last Notebook,” is a remarkable creation.

On its own, the recreated sketchbook — which duplicates the original’s trim size, color, trace paper, (many) empty pages, and even a small smear of ink on the cover — delivers an intimate reflection of, and connection to, an architect who could embed physical objects with deep feeling; carving out space, light and spirit. (An accompanying volume lends context and clarification.) The grace and clarity of his images and thoughts are amplified by the accuracy and tactility of the facsimile. They have a more personal impact when you notice the outline of your fingers behind each page, as if you’d stumbled onto his notebook in a drawer. You can tell how hard Kahn was pressing his pencil to craft a drawing, or how carefully — or quickly — he was trying to compose an idea.

“The notebook is for a man on the move,” Michael J. Lewis, an architectural historian who wrote the introductory essay for the companion book, pointed out in a recent interview. “Normally he’d be in the office working on yellow trace. He’s not working in the sketchbook unless he’s on a plane or train or in a hotel room. It makes it less formal, less self-conscious.”

Here are eight discoveries about Kahn, his work, and his life, among many to be found in the notebook’s drawings and notes.

“Trying to evoke the life of things.”

The weighty blocks of the Roosevelt Memorial, which Kahn energetically outlined throughout the notebook, are almost animate. I’ve been to Four Freedoms Park, and the drawings teleported me to the windy southern edge of Roosevelt Island. Conceived on the go, they are not hyper-accurate depictions. They capture instead the feeling of Kahn’s plans. Sketching quickly, he focused on core components and rendered others lightly, abstractly. The blocks where Roosevelt’s statue would stand are rendered with frenetic motion and heavy dark pencil, pulling you toward them; nearby walls are virtually see-through, supporting characters in the drama. Kahn’s language was mass and light and shadow, and the stillness between them; it translated on paper just as it did in stone and concrete.

“I think he was a poetic soul,” Sue Ann noted. “He’s trying to evoke the life of things,” Lewis said. “He’s engaged in detailing his buildings right to the end.”

Searching for ideas via drawing

In his introduction, Lewis described the evolution of the Roosevelt Memorial and how Kahn originally planned for the project to culminate with a “bastion,” a tall, temple-like outdoor room formed of 60-foot-tall, stainless-steel-clad concrete walls, looming over a statue of Roosevelt. The concept was later pared down to a 12-foot-tall, stone-clad room, with a bust of Roosevelt that is practically the same height as the walls. We’re reminded of the nuts and bolts of architecture — how legends, too, are susceptible to so-called value engineering. Kahn has to scramble to redevelop his design, revealed later in a fever of notebook pages.

We also get an intimate sense of Kahn’s design process — how he uses drawing as his primary way to develop concepts. “He’s searching for an idea through his drawings,” Lewis said. “The sense of exaggerated scale. The notion of this fortified surrounding, which could be nodding to New York’s early fortified walls.” He added: “There’s a nonstop conveyor belt of ideas going through his mind.”

As Sue Ann noted: “He was never not drawing. From the time he could barely hold a pencil he was visually having creative thoughts about the world.”

Contemplating awe and wonder

Kahn’s confident script, together with notes he scribbled on top of drawings, brainstorms and the drafts of speeches — including arrows, underlines and circled phrases — reveal how he was thinking and evolving. In some cases, Kahn writes complete paragraphs. In others, he employs diagrams to outline ideas, leaving words disembodied.

In his notes for a lecture at the University of Maryland, Kahn explores (seen on the top of the right hand page) how architecture can instill wonder and revelation — a return to our very first sensations. It’s an approach that helped him root his modern designs in the presence and profundity of ancient buildings.

“It’s about a sense of awe and wonder. An encounter with the sublime,” Lewis said. “It took him into his 50s to put it all together.”

On a quest for “the aura of the inspirations”

Just as Kahn used drawings to develop his ideas, he used words to inform his drawings. (Lewis likens Kahn’s seamless connection between thought and illustration to a kind of synesthesia.) The notes above are a draft of Kahn’s acceptance speech (written on the train from Philadelphia) for the Gold Medal at the American Academy of Arts and Letters, in New York. Kahn, who constantly riffed on the emotional and spiritual power of buildings, was honing in on his work’s connection between “silence,” which he here calls “the desire to be, to express,” and “light,” which he often equated to the fulfillment of that desire. The meeting of the two, he notes farther down, is “where poetry lies.” Or “the aura of the inspirations.”

“You don’t take this as a fully fleshed out philosophical program,” Lewis noted. “It has a searching quality that’s similar to his drawings.”

On the left hand page, opposite his notes for the speech, Kahn asked colleagues at the acceptance ceremony to write their names and addresses into the book. This is a reminder of Kahn’s busy networking; an intrusion of everyday life into the sketchbook’s realm of the ethereal.

Love beyond accepted norms

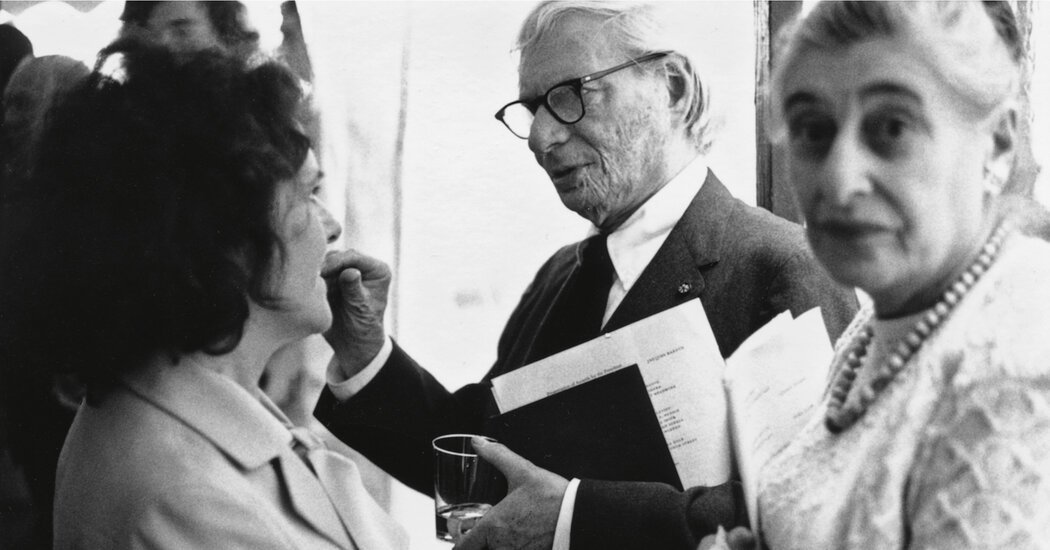

Sue Ann has included, in the companion book, a picture of her father at the academy lecture, a cocktail glass in hand, with a mischievous smile, and the notebook under his arm. “He was an ambassador of creativity and art,” she said. “He loved people and people loved him.”

One thing the notebook does not reveal, Lewis said, is how this love could (infamously) extend beyond accepted norms, as chronicled in the documentary “My Architect: A Son’s Journey”(2003) by Nathaniel Kahn, Sue Ann’s brother. “Harriet Pattison (one of Kahn’s two mistresses with whom he had children) and he are working eyeball to eyeball this last year of his life,” Lewis added. “What is missing here is the conversations with her.”

“It was no secret, his private life,” Sue Ann said. “Everybody knew about it. But people didn’t talk about it. My parents had their thing that they worked out and that was that.” She added: “My father would say ‘I want to tell you about everything,’ but he never would.”

Channeling the landscape

In the supplementary volume, Sue Ann has incorporated a picture of the soft, eroded foothills of the Alborz Mountains, just outside Tehran, which inspired her father’s undulating drawings for Abbasabad. It’s a peek into the prime role of topography in Kahn’s work, making it feel of a place, albeit abstractly.

In his essay, Lewis notes how Kahn’s last drawing for Abbasabad — a plan of the whole site — looks remarkably like a human face in profile. Perhaps, he wonders, it’s an explicit realization of Kahn’s humanist approach, on a massive scale?

Finding delight in fantasy and whimsy

The last image in the book, a playful spark of light, is most likely Kahn’s attempt to represent the glint of sunlight that would appear at certain times of the day in the space between concrete walls at Four Freedoms Park. But it also sums up the wonder with which he practiced and lived. “He loved the idea of fantasy and whimsy and talking to young people,” Sue Ann explains, comparing the drawing to the stars of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s “The Little Prince.”

In his essay, Lewis notes how Kahn’s last sketchbook “brims with the drive, ambition, and restlessness we associate with youth.” He calls the spark “a lone sparkling star with a line leading to it, as if summoned forth by the wand of a magician who has already disappeared.”

Some might consider calling an architect a magician an insult, as though he were performing tricks onstage or at parties. But it’s a perfect description of Louis Kahn, who could bring matter to life, and lift our spirits in the process.