“When he died, something entered into me which I cannot describe,” Baldwin wrote in the notes for the play. “I resolved that nothing under heaven would prevent me from getting this play done.”

Otherworldly resolve would be necessary to actualize his artistic endeavor because Broadway was dominated by white theatermakers and audiences. Baldwin therefore didn’t trust, or fully respect, the American theater, and soon became frustrated with his white producers, notably when they resisted his insistence on reducing ticket prices so that more Black audiences could attend — a necessity to achieve his artistic ends. “Blues” wasn’t “a Negro play,” or just about “civil rights,” he said, but “about a state of mind and relationship of people to each other.” To access this meaning, white and Black theatergoers must be in the room together. “I want to shock the people,” he said, adding, “I want to trick them into an experience which I think is important.”

Among shows that challenged Broadway’s demographics was Lorraine Hansberry’s “A Raisin in the Sun” (1959), the first play by a Black woman on Broadway. Baldwin met Hansberry in 1958 during the “Giovanni’s Room” workshop, which began their “intimate intellectual companionship,” as described by the Hansberry scholar Imani Perry. His affection for her is noted in “Sweet Lorraine,” an essay written after her death in 1965. In it, Baldwin recalls her importance to the stage, and notes that he had never seen so many Black people in the theater before “Raisin” — they had ignored the theater, he wrote, “because the theater had always ignored them.”

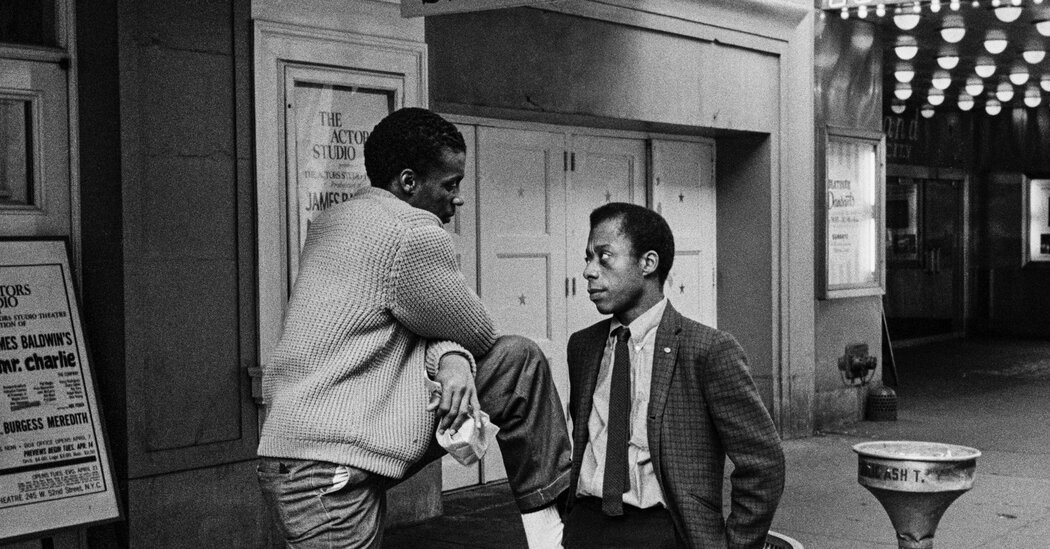

ON APRIL 23, 1964, “Blues” opened at the ANTA theater. The plot follows Richard, a young, outspoken Black musician returning home to the South, to “Plaguetown,” a name that casts an allegorical sheen over the story. He is murdered by a white racist shopkeeper, and a sham trial ensues, exposing the diffidence of the drama’s white liberal character. The staging racially segregates the townspeople, which juxtaposes, and charges, the mixed, intimate audience, said Leeming, who attended the premiere. Everyone “came to the play with very different possibilities, very different hopes, very different fears,” he recalled. “That’s what made it so terrifying and moving.”

Reviews were critical — with The Village Voice claiming it “falls into the traps of all propagandistic art” — though The New York Times was favorable, seeing “fury in its belly, tears of anguish in its eyes.” The negative reviews upset Baldwin, but he believed he had achieved his goal, Leeming said, and believed white liberals’ discomfort proved the play’s relevance.

Read More: Baldwin’s ‘Blues for Mister Charlie,’ 60 Years After It Hit Broadway