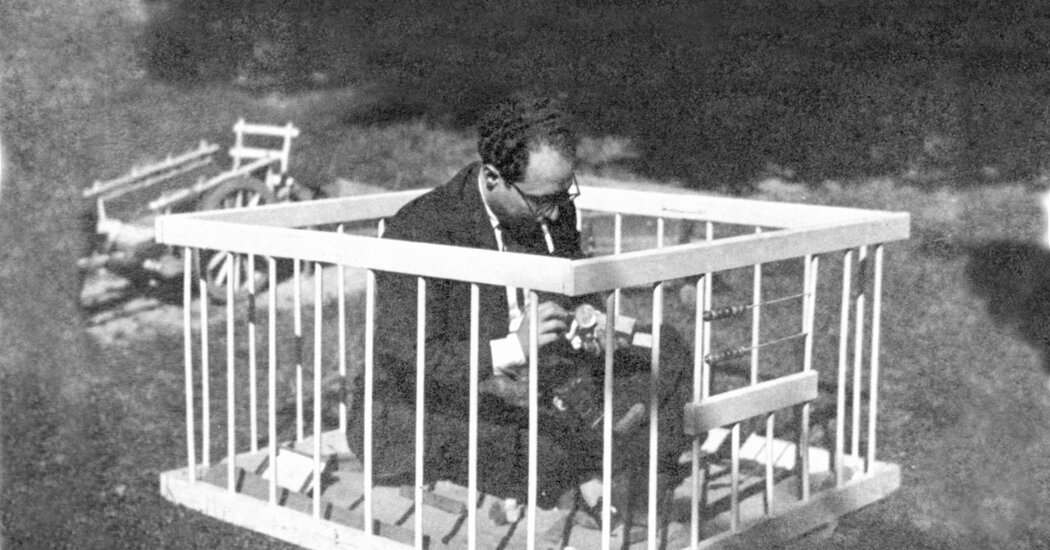

A black-and-white snapshot from around 1945 shows a man with twin shocks of hair sitting in a child’s playpen, a cigarette between his lips. This is Francesc Tosquelles, a psychiatrist who spent decades dismantling the hard bars between illness and health, pathology and normalcy, artists and everyone else. He drew on Freud and Marx, and also on his experience as a refugee, in exile from Franco’s fascist Spain.

The photo appears in “Francesc Tosquelles: Avant-Garde Psychiatry and the Birth of Art Brut,” an exhibition at the American Folk Art Museum that traces the career and influence of this Catalan doctor. Against the historical trauma of fascism, war and displacement, Tosquelles built radical psychiatric practices around non-hierarchical relations between patients, doctors and their neighbors.

He also encouraged his patients’ creativity, which put him at the confluence of Modernist avant-gardes and Art Brut. All these ideas converged at a psychiatric hospital in Saint-Alban, a small village in southern France, where Tosquelles worked from 1940 to 1962.

The craft of the objects can be stunning, with a raw intricacy that speaks to their makers’ intensive attention. An elaborate scrapwood boat carved by Auguste Forestier, complete with anchor and crew, opens the show. A lustrous alpine scene embroidered by Marguerite Sirvins depicts a jagged paradise of hunters and prey. Both were patients in the Saint-Alban hospital.

Tosquelles’s career helps organize a subject — self-taught artists — whose boundaries are still frequently debated. Video clips from a 1987 interview with the doctor, patiently unpacking his thinking in an overflowing office, help break the show into sections, like “Exile” and “Disalienation.” Still, it can be confusing how or if certain artists ever crossed paths with Tosquelles, or whether that matters.

One room displays three oil portraits by a Saint-Alban patient who may have been simply hiding from the Nazis; a section of a collaged frieze by a patient at another French hospital; and three photographs of Parisian graffiti by Brassaï. These accompany Art Brut mainstays like sinuous reliefs carved in cork by Joaquim Vicens Gironella, or rhythmic abstract paintings by Henri Michaux, who self-induced “psychosis” by taking mescaline. One highlight of the show is a bulbous, gouged painting by Jean Dubuffet titled “Antonin Artaud With Tufts,” showing Artaud, the frequently hospitalized poet, on a dramatic hair day.

During the German occupation of France, Saint-Alban was something like an artists’ colony. Picasso paid a visit, as did the Dadaist writer Tristan Tzara. Dubuffet, the impresario behind the term Art Brut, came knocking in 1945, hoping to take home a piece by Forestier.

He didn’t get one. In fact, Dubuffet and Tosquelles clashed over how outsider artists should relate to society.

Dubuffet and his fellow avant-gardists valued what they called “art of the insane” for the same reason they collected objects by children and so-called primitive cultures: They saw much of Western culture as dehumanizing, and sought to repudiate the standards of a sick, warmongering society. Many modernist artists romanticized conditions like schizophrenia, and didn’t dwell on the lived experience of those with mental illness.

For Tosquelles, his patients’ art making aided their participation in society. He helped develop institutional psychiatry, working against what he saw as doctors’ fears of illness, which led them to lock up and straitjacket their patients. Tosquelles saw himself as equally alienated — posing within a playpen’s bars.

He took the bars off the Saint-Alban windows and let his patients roam the village, chatting with townspeople, even trading and selling what they made. A “patients’ club” organized plays, publications, films and outings.

Tosquelles also instructed his colleagues in psychoanalytic concepts and trained local people in basic psychiatry. With fascists on the march and decades of unthinkably brutal war, it seemed clear to Tosquelles that just about everyone needed therapy. If the affliction is social, he reasoned, the treatment must be too. Tosquelles disdained doctors who, as he put it in a 1982 interview, “think that they can cure the world with a pill.”

For the most part, 19th-century “asylums” in the United States earned their ill reputes. As the 20th century unfolded, American psychiatric hospitals were often closed rather than reformed, especially after the dawn of antipsychotic drugs including Thorazine in the 1950s. Treatment tended to be solitary — you don’t need community, you need your meds.

The exhibition’s final section names the thorny question that haunts the fascination with institutionalized artists: Is mental illness a worthwhile price to pay for creativity?

One of the most expansive objects in the show, in a group of works from the United States, is a flared cloak covered in pale blue curls, heart-shaped groups of figures and illegible letters, so thickly embroidered that it seems to be made entirely of stitches. Its maker, a woman named Myrllen, reportedly experienced symptoms of schizophrenia, and was one of the first Americans prescribed Thorazine. Her harrowing hallucinations subsided, but so did her desire to sew.

Tosquelles’s approach was closer to that of the Creative Growth Art Center, founded in Oakland, Calif., in 1974, where neurodivergent adults spend their days making art in communal settings and have input in how it circulates.

The show concludes with two pieces by Judith Scott, an artist with Down syndrome who practiced at Creative Growth and died in 2005. Her abstract, vivid sculptures, made from wrapped miles of yarn, tubing and textiles, can resemble cocoons or bodies. Gathering, touching, connecting — these are Tosquelles’s methods.

Francesc Tosquelles: Avant-Garde Psychiatry and the Birth of Art BrutThrough Aug. 18. American Folk Art Museum, 2 Lincoln Square, Manhattan; 212-595-9533, folkartmuseum.org.

Read More: The Avant-Garde Psychiatrist Who Built an Artistic Refuge